The cause of migraines is unknown, but research is now pointing to genetics as the cause of migraines. Genetics relates to the DNA that you inherit from your parents, as well as the way your genes are expressed in response to environmental, biological and nutritional factors that can act as the triggers of attacks.

Over the years, theories and hypotheses about the cause (pathogenesis) of migraines have been vigorously debated among researchers and healthcare professionals. Theories range from cortical vasodilation, brain energy deficits, brain oxidative stress, visual cortex hyperexcitability, and thalamocortical dysrhythmia theories. An older theory, that has since been invalidated, is the vasospasm theory. This theorised that the cerebral blood vessels constrict and reduce perfusion throughout the attack. Hypoperfusion does occur during a migraine attack with aura, but this is followed by hyper-perfusion during the headache phase, before returning to normal perfusion during the attack. One reason why there are so many theories is due to the multifactorial nature of migraines — the threshold for an attack can be influenced by a great number of variables that differ between people. Elements of all theories are known to occur, including vasoconstriction, vasodilation, brain energy deficits, oxidative stress, cortical hyperexcitability and dysrhythmia. All of these rely on genetic expression to create enzymes, hormones, neurotransmitters, and proteins, and explain the pathophysiology of attacks, but not the pathogenesis.

Triggers vary greatly, and commonly include foods high in tyramine, fermented foods, alcohol and caffeine, as well as stress, disturbed sleep and poor eating patterns. Triggers are contentious because some of them may simply be cravings in response to changes in blood sugars and hormones that occur during the prodrome phase at the start of an attack, but wrongfully blamed as a trigger. Chocolate has commonly been reported as a trigger. Researchers studied people who reported chocolate as a trigger, and found that chocolate didn’t trigger attacks. Research is also pointing to attacks being triggered by multiple triggers acting at the same time. It appears that many people have a threshold that can tolerate one or two triggers, but when multiple triggers act together this threshold may be exceeded, triggering an attack.

The hypothalamus becomes dysfunctional early in an attack. This dysfunction manifests with food cravings, altered sleep patterns, stress, yawning, and changed sexual behaviour. All of these are governed by the hypothalamus. Many of these are considered to be triggers, but may not be triggers at all. They may be early signs and symptoms of hypothalamic dysfunction that occurs during the prodrome of an attack, signalling that an attack has already started.

Another known cause is mild traumatic brain injury, such as concussion. Some people that experience concussion develop migraines for the first time. Post-concussion migraine is more common in those with a family history of migraine. Migraine attacks are triggered by factors that affect gene expression in your body. Attacks can be triggered by:

- Dietary factors

- Environmental factors

- Biological factors, such as hormones, immune, physical and emotional factors

Your biological systems contribute to initiating and sustaining migraine attacks. The influence of each of these systems differs among individuals, and may vary over time. The degree of influence of each of these systems varies between people. This is one of the reasons that pharmaceutical prescriptions aren’t effective for many people. They only target a small part of one, maybe two systems. These systems communicate with each other through complex biochemical reactions, and include:

- Gastrointestinal (digestive) system

- Musculoskeletal system

- Immune system

- Endocrine (hormone) system

- Central nervous system

What are the symptoms of a migraine?

The signs and symptoms of a migraine are highly variable due to the multiple systems involved in attacks; headaches are just one of many symptoms you can experience.

There are 2 types of migraine:

- Migraine without aura. This is the most common, affecting more than 80% of people who suffer migraines

- Migraine with aura

Migraines may occur as infrequently as a few times per year, to multiple attacks weekly. Chronic migraines occur on 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, with headache on at least 8 days per month.

Auras are neurological signs and symptoms that occur with an attack. They are temporary and reversible:

- Visual disturbances are the most common, affecting 99%

- Vertigo affects 30–50%, known as a vestibular migraine

- Sensory disturbances, such as numbness, pins-and-needles or tingling affect 31%

- Speech or language disturbances affect 18%

- Movement disorders, such as difficulty moving or co-ordinating muscles and limbs affect 6%

Migraines usually last 4–72 hours and include at least 2 of the following:

- 1-sided (unilateral) pain or headache

- Moderate to severe intensity

- Throbbing pain

- Pain aggravated by movement

Combined with at least 1 of the following:

- Nausea, which affects 80%

- Vomiting, which affects 50%

- Increased sensitivity to light (photophobia) affects 90%

- Increased sensitivity to noise (phonophobia) affects 75%

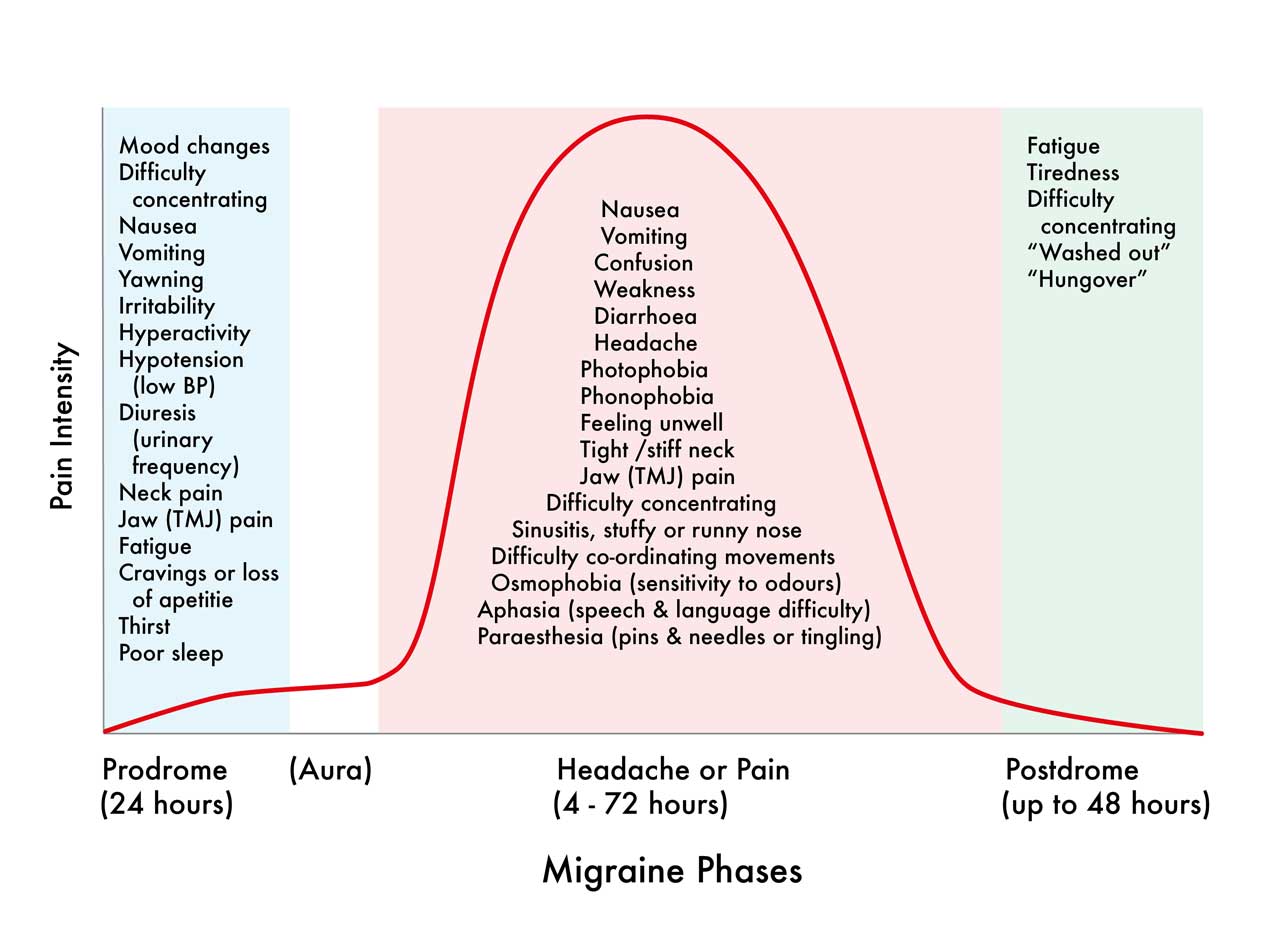

Migraine attacks occur in phases. Symptoms are variable and can overlap between phases:

- Prodrome symptoms precede the headache phase by 24—72 hours. These signal an impending attack

- Aura symptoms are only experienced by those who suffer migraines with aura. Symptoms occur in close succession or at the same time, lasting 5 minutes or more

- Headache or pain phase

- Postdrome phase usually lasts up to 48 hours, but may last several days. Some people don’t experience this phase

The prodrome that precedes an attack commonly involves fatigue, yawning, difficulty concentrating and remembering things, mood changes and neck pain. These usually start about 24 hours before an attack, but may persist during the attack. Some people also experience red eyes, tearing, congested sinuses or runny nose, and temporomandibular disorder (TMJ pain). This is because the face, eyes, nose, sinuses and jaw share innervation with the trigeminal nerve, which also innervates the meninges around your brain. The trigeminal nerve is known to be involved in an inflammatory and immune response during an attack. The trigeminal nucleus is found in the brainstem, alongside other nuclei that control nausea and autonomic nervous system responses, amongst many others. The brainstem is also highly connected to the thalamus, which significantly influences sleep and eating, blood sugar control, metabolism, and a myriad of other important functions.

The migraine attack commonly includes a severe headache to one side of the head. The nervous system is hypersensitive during the attack, causing aversion to bright light (photophobia) and loud sounds (photophobia). The severity will often cause someone to seek a quiet dark place to lie down, and stop them from daily activities such as work. There may also be intense nausea and vomiting due to activation of the area postrema of the brainstem. The attack typically lasts up to 72 hours, but may persist longer. Once the attack subsides there may be a postdrome, which feels like a hangover.

This is a common pattern for the most common phenotype of migraine: a migraine without aura. Some people experience aura symptoms during the prodrome, or even alongside the attack. The aura symptoms persist longer than 5 minutes and can include visual disturbances, such as flashing lights or blind spots, sudden onset of numbness or tingling to the face or limbs, and speech or language disturbances. These symptoms are temporary and reversible.

How are migraines treated?

Your practitioner will take a detailed history and assess the function of your immune, gastrointestinal, endocrine, musculoskeletal and nervous systems to determine the extent of their involvement. They will perform a physical examination to help rule out other causes of your signs or symptoms, and may also perform orthopaedic and neurologic exams. There are no blood tests or imaging biomarkers that are useful for diagnosing migraines, unless there is an underlying clinical suspicion of a pathological cause, such as trauma or infection.

Migraines cannot be cured. Signs and symptoms vary between people due to the differing influences of diet, environment and biology on each person. Most migraines are also polygenic, involving multiple genes, which also differ between people. This is why multi-modal treatments have higher success rates.

Research shows that the frequency, intensity and duration of migraine attacks can be improved with appropriate manual treatments and exercises, occupational and lifestyle strategies, dietary and nutritional medicine, and herbal medicine. Pharmaceutical medications help some people, but most are only moderately effective at best. Some people don’t like taking medications. Some don’t like the side-effects, or can’t tolerate them. Others worry about their safety. Some medications cause a medication overuse headache, which can occur at the same time as the migraine it’s supposed to treat (medication overuse headache is the 3rd most common headache in the world). Due to the multifactorial nature of migraines, and the many different body systems involved in attacks, a multimodality approach offers the best treatment option with the highest likelihood of success.

Migraines treated unsuccessfully can evolve into chronic migraines. These significantly reduce your quality of life and health. They can affect work performance, as well as family and social relationships. They can also stop you enjoying activities you love, such as sport and exercise.

You can book an appointment online or call The Headache and Neck Pain Clinic today to make an appointment.

You can also download a Headache Diary and a Migraine Triggers and Symptoms Questionnaire here.

If you experience visual aura with your migraine you can download a Visual Aura Table with descriptors from our website, or you can download the table from the International Headache Society website, thanks to the generosity of the International Headache Society and Dr Michele Viana and colleagues for sharing these images and allowing free circulation.