What Are The Causes Of TMJ Pain?

Head or neck injuries, or prolonged postures can cause temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain and temporomandibular disorder (TMD). This is because all of the muscles responsible for stabilising and moving your jaw attach to your head and neck, so head or neck injuries or dysfunction can cause problems with your jaw.

The most common cause is prolonged postures, such as slumping in front of a work computer. This slumped position causes your head and neck to protrude forward, stretching the muscles that attach from the front of your neck to the underside of your jaw, restricting your jaw movement.

TMJ pain and dysfunction is also caused by trauma, such as hitting your jaw or face, or whiplash to your neck. This can happen in car crashes or collisions in sport. TMD affects more than 20% of people with whiplash.

It can also be caused by dental problems that cause misalignment of your bite pattern, or malocclusion, as well as holding your jaw wide open for a prolonged amount of time at your dentist.

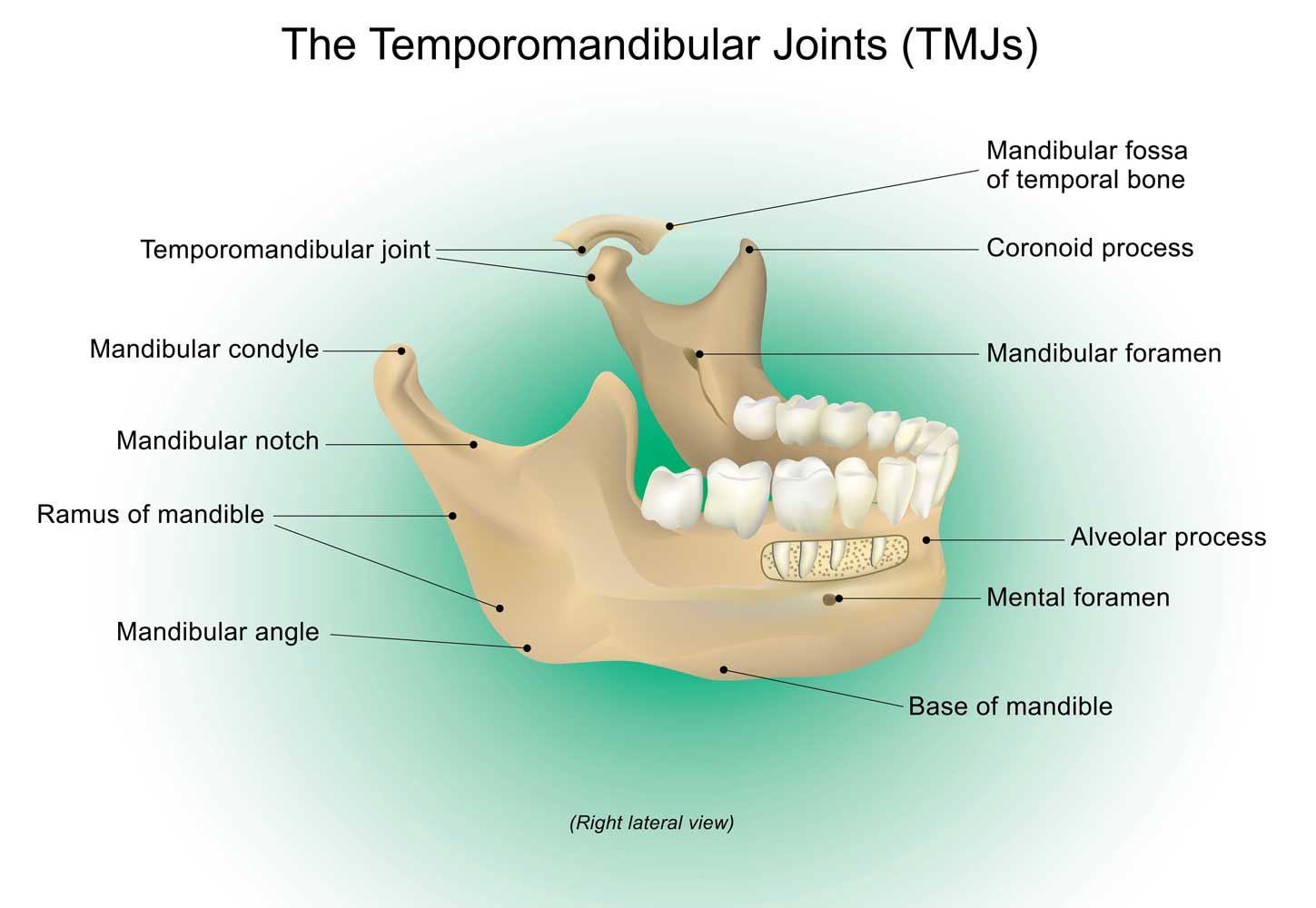

The TMJs are the most complex joints in your body. A multiplex of muscles opens, closes, protrudes, retracts and moves your jaw sideways. As you open your mouth your TMJs hinge open. Your TMJs then glide forward on small discs that allow your jaw to slide forward so that it can fully open. These discs are held and guided by ligaments that allow the discs to slide forwards and backwards with your TMJs. The discs and TMJs move independently of each other, but when functioning correctly they co-ordinate their movements together. This also protects the joints from degeneration.

Prolonged postures that cause your head and neck to protrude forward stretch the muscles on the front of your neck that attach to your jaw. When these muscles are pulled tight they resist your jaw gliding forward to fully open. Over time this can cause pain and dysfunction of your TMJs. It can also cause your TMJs to slip off the discs when their movement isn’t co-ordinated, making a popping or clicking sound. This is known as “disc displacement”. When you close your mouth your jaw moves back to its original resting position. As it does this, your TMJs reposition themselves correctly on their discs. This repositioning is known as “joint reduction”, where the joint reduces back to its correct position. The process of displacement and reduction is known as “disc displacement with reduction”. If your TMJ doesn’t reduce back onto the disc it is known as “disc displacement without reduction”. When this happens the disc can buckle and jam around your TMJ, causing pain, restricted movement or locking.

The most common cause of TMJ pain and dysfunction is “myogenic” temporomandibular disorder (TMD), which is due to pain and dysfunction of the muscles that stabilise and move your jaw. The second most common cause is mixed” TMD, which involves pain and dysfunction of both the muscles and jaw joint (TMJ). The least common is “arthrogenic” TMD, which is caused by pain and dysfunction of the jaw joint (TMJ).

What Causes TMJ Disorder (TMD)?

- Misalignment of the bite pattern (malocclusion)

- Overuse

- Osteoarthritis

- Bruxism (teeth grinding)

- Trauma (including trauma to your neck)

- Chronic neck pain

- prolonged forward head and neck postures

- Some medications and recreational drugs

- Disorders of the jaw muscles

- Displacement of the discs in your TMJs

- Headaches and migraines

What Are The Signs And Symptoms Of TMJ Pain And Dysfunction?

Your TMJs and some of your jaw muscles are innervated by the trigeminal nerve. This nerve also innervates your face, teeth, ears, sinuses, and the outer layer around your brain (meninges). TMD can cause pain in these other areas; it can mimic a toothache, an earache, or cause headaches. If the trigeminal nerve becomes irritated it can set off inflammation in other parts of the trigeminal nerve. If this happens in the part of the trigeminal nerve that innervates your meninges you can experience a headache. This is inflammation of the trigeminal nerve and the meninges inside your skull, and is known as an intracranial headache. TMD can also cause muscle pain (myalgia) in your masseter muscles on either side of your jaw, as well as your temporalis muscles that attach your jaw to your temples. These are very strong muscles that close your jaw, and they have to work hard when chewing. Myalgia can cause pain to your TMJs and temples, causing a headache from outside your skull (an extracranial headache). A skilled clinician can differentiate these, because the treatments are different.

Just as TMD can cause headaches, the opposite is also true. People who suffer 4 or more headaches per month are more likely to develop TMD. People who suffer tension headaches are 3 times more likely to also suffer TMD, and people who experience migraines are 10 times more likely to also have TMD. Signs and symptoms include:

- Headache

- Earache

- Pain in front of the ear, around the ear, or to the temples

- Tenderness of the muscles involved in chewing (mastication)

- Dental pain (it can mimic a toothache)

- Pain when chewing or speaking

- Clicking and popping, or fatigue when chewing

- Limited opening or closing of the mouth

- Lockjaw (trismus)

- Ringing or roaring in the ears (tinnitus)

- Neck pain and dysfunction

- Hearing difficulties or ear fullness

- Dizziness or imbalance

- Inflammation of the lining of the nose (rhinitis)

- Dry eyes (xerophthalmia)

What Is Tinnitus?

Tinnitus is a perceptual phenomenon. It is a sensation of hearing a ringing or roaring sound despite the absence of such sounds. There are various underlying causes, and it impacts approximately 10-15% of adults. Dental pain or TMD are commonly associated with tinnitus. This is especially true in cases of advanced TMJ pathology.

87% of cases of TMD are associated with symptoms related to the ear. These are referred to as otological symptoms. They include tinnitus, deafness, dizziness, imbalance, or ear fullness. Tinnitus is the most prevalent of these symptoms, affecting around 42% of people with TMD. Ear fullness affects approximately 39% of people. Unfortunately, 78% of those who suffer from TMD with otological symptoms are women.

Up to 43% of people who experience tinnitus also have neck or jaw dysfunction. This is common with “somatosensory tinnitus”. The loudness or pitch of the tinnitus temporarily changes with movements of the jaw or neck. Eye movement can even change the loudness or pitch in some people. How tinnitus occurs in the brain is still mostly a mystery. Animal studies have shown that sensory signals from the upper cervical spine (the spinal trigeminal nucleus) have the ability to silence self-produced sounds of tinnitus in the brainstem (at the dorsal cochlear nucleus). Sensory nerves from the upper cervical spine synapse in the spinal trigeminal nucleus. This may explain why neck or TMJ problems can cause tinnitus, due to an impaired ability to cancel out the self-produced sounds of tinnitus.

How Is Jaw (TMJ) Pain Treated?

Your practitioner will take a detailed history and perform a physical examination to diagnose the cause of your TMJ pain. They will assess your posture and movements, including your neck which can affect the function of your jaw, looking for painful or dysfunctional postures and movements. You may be referred for imaging if there is an underlying cause such as trauma.

You will be given a diagnosis. The most common cause of TMJ pain and dysfunction is “myogenic” temporomandibular disorder (TMD), which is due to pain and dysfunction of the muscles that stabilise and move your jaw. The second most common cause is mixed” TMD, which involves pain and dysfunction of both the muscles and jaw joint (TMJ). The least common is “arthrogenic” TMD, which is caused by pain and dysfunction of the jaw joint (TMJ). You will be presented with recommended treatment options. The recommended treatments will be tailored specifically to your TMJs and neck, and will be discussed with you so that you are comfortable with the treatment approach. Manipulation (also called adjustment) may be recommended, but if you are not comfortable with this then other techniques can be used.

Research shows that TMD responds well to manual treatments and exercises, such as joint manipulation (adjustments), mobilisation, dry needling, soft tissue treatments, muscle energy and neuromuscular inhibition techniques, and stretches. The treatments and exercises aim to reduce tight muscles, stretch short muscles, and strengthen weakened muscles or muscles that need more endurance. The treatments and exercises will also strengthen muscles essential to neck and head stabilisation, and restore correct and accurate movement to your TMJs that are not moving correctly.

TMD doesn’t only affect the parts of your brain associated with the perception of pain. It also affects other areas that regulate your emotions and mood, cognition (your ability to concentrate and remember things) and your social and professional interactions. Research shows that people who experience chronic TMD have higher levels of anxiety, depression and poor sleep. Every person is different — it affects some people more than others. This is known as the biopsychosocial framework, which considers the biological, psychological and social effects of TMD on you, as a whole person. This is also taken into account with your treatments.

Analgesic (painkiller) and anti-inflammatory medications have a mixed track record, working for some but not others. Importantly, medications won’t fix your underlying functional, stability, or postural problems. Rehabilitation exercises and stretches are prescribed specifically tailored to you, and the problem with your TMJs. You will also be given occupational and lifestyle strategies. All of these are designed to get you out of pain, improve function of your TMJs, and reduce the probability of recurrence.

Treatments are focussed on the underlying cause and not simply providing short-term relief. Many people are pain-free within a couple of treatments. The research, and experience shows that other people may take between 6—12 weeks. This is common if the underlying cause has been present for a long time. Strengthening and retraining muscles and restoring correct, accurate function to the neck and jaw takes time. There are no quick fixes. Some people only want to get out of pain, and we respect that decision. We will always recommend treatment and exercises that are specifically tailored to you and your needs, with the aim of getting long-term, lasting results for you.

You can book an appointment online or call The Headache and Neck Pain Clinic today to make an appointment.